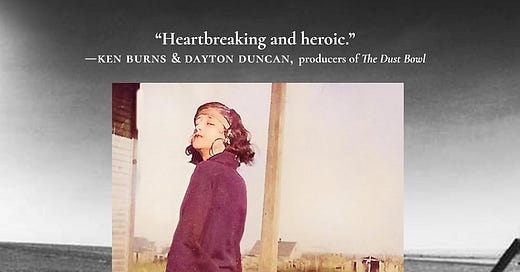

Books: Whose Names Are Unknown by Sanora Babb

Resurrecting the voice of a forgotten woman writer.

My copy of

’s Riding Like the Wind: The Life of Sanora Babb is arriving sometime today. Published October 15th, the book is a “saga of a writer done dirty” and “resurrects the silenced voice of Sanora Babb, peerless author of midcentury American literature.”I’m especially excited about this book because I know of Babb, but Dunkle has done the deep, deep dive that’s going to let me and the rest of the world truly know Babb’s story. One of my creative nonfiction professors at UC Riverside Palm Desert, Deanne Stillman, told me about Babb five years ago. I read and then wrote a review of Babb’s novel, Whose Names Are Unknown, for one of my fiction classes, and I included Babb’s story briefly in an essay I wrote for the Los Angeles Review of Books: “Ghosts on the Page: Alice Cary’s ‘Hagar: A Story of To-Day’ and Other Lost Books.

Today, I’m sharing the review I wrote of Babb’s 1938 novel. It’s a true California story for me. I am a writer whose family came here from Oklahoma during the Dust Bowl era and whose own voice has been influenced by John Steinbeck as well as the forgotten voices of women writers like Babb. I hope reading this inspires you to read Dunkle’s book to learn more about Sanora Babb, a remarkable woman and an incredible writer. I hope you’ll read Babb’s book, too, and help her voice rise up again from the dust.

Sanora Babb was born in Red Rock, Oklahoma, in 1907. She wrote Whose Names Are Unknown in 1938 based on her experiences growing up on a broomcorn (sorghum) farm, later visiting family who still lived in Oklahoma during the Dust Bowl and helping Dust Bowl migrants in California when she worked for the Farm Security Administration. Babb’s 1938 novel was not published until 2004—it was lost to the public for sixty years.

Babb’s family history echoes my own. Both sides of my family came to California’s Salinas Valley in the 1930s and 1940s. Both sides of my family were poor. My grandfather worked as a farm laborer and eventually became a ranch foreman in Soledad. My grandmother worked in the vegetable packing sheds. People called them “Okies” and “Arkies.” My father’s family were migrant farmworkers. They came from Arkansas and traveled from place to place picking fruit for a living, depending on the season and the weather. People called my father’s family “prune pickers” and “fruit pickers.”

A generation later, I was born in a small town called King City. The town is located in Monterey County, California, at the southernmost end of the Salinas Valley. John Ernst Steinbeck, Sr., helped settle this town in 1890, and his son and namesake set his novel East of Eden here in 1952. I grew up reading Steinbeck’s stories and thinking The Grapes of Wrath, which won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1939, was the definitive novel about the experiences of families like mine: Okies and Arkies who tied their belongings on top of their trucks and came to California’s fertile valleys to escape choking dust and a hardscrabble life, only to find themselves looked down upon, called names, and living in deplorable conditions. I only learned about Babb’s book last year. Reading the two books alongside one another is a unique experience.

Babb is a woman I would have loved to meet for beers. She exiled a smitten William Saroyan to the friend zone, had an affair with Ralph Ellison, and was blacklisted during the earliest days of the anti-communist investigations. Babb was forced to live apart from her Chinese American husband, James Wong Howe, an Academy Award-winning Hollywood cinematographer, for ten years, due to California’s anti-miscegenation law. Her first novel, Whose Names Are Unknown, was shelved by Random House publisher Bennett Cerf when John Steinbeck published The Grapes of Wrath in 1939. It was too similar, her publisher told her.

Only later did it become apparent that Babb’s supervisor at the FSA had shared Babb’s journals with Steinbeck without Babb’s knowledge or permission. Steinbeck used Babb’s notes, along with his own experiences and sources, to write The Grapes of Wrath. Babb was crushed and didn’t publish anything for the next twenty years. Whose Names Are Unknown wasn’t published until 2004, a year before Babb died, and is still relatively unknown. There is a great deal of controversy surrounding this. There are many who do not believe Steinbeck plagiarized Babb. They argue that her notes were just one of many sources he utilized in his extensive research for the book and that John Steinbeck certainly didn’t need to plagiarize anyone.

But, without taking away from Steinbeck’s work, Babb’s novel has something different to offer. It carries the weight of truth and experience. Steinbeck read the notes and then imagined from them, albeit beautifully. But Babb lived them. When I skim back through The Grapes of Wrath now, I see a masterfully written story deserving of all the praise and attention it received. However, by all accounts, Steinbeck’s family was well-to-do. Steinbeck worked alongside migrant farmworkers in the summer, like my grandfather sometimes had me do when I was young. But like me, he did so from a place of privilege, and he was born in California and was not a migrant himself.

The difference shows when I read Babb’s novel, which breaks my heart and which, for me, packs a more significant emotional punch. Steinbeck’s novel is an epic set mainly in California—within the first few chapters, the Joad family has left Oklahoma. Babb’s novel is half as long as Steinbeck’s and is simpler, more succinct. About two-thirds of Babb’s novel is devoted to the devastation that led several families to leave the Midwest. In Steinbeck’s novel, the characters and the plot are most significant—although Steinbeck does devote significant time to describing the California valleys where the migrants settled (the places in which Steinbeck grew up and with which he was familiar), the Oklahoma chapters are not as detailed as Babb’s with respect to place.

Steinbeck is a master of place, and locations in his books are characters in and of themselves. The Grapes of Wrath is no different, but in Steinbeck’s novel, California is the place, and the events which make up most of the novel are those which take place after the Joad family has left Oklahoma and migrated to California. In Babb’s book, equal time is spent describing life in both places, and Babb in fact lived in both places and lived both lives.

The details Babb provides are so personal and so evocative because she experienced the lives she’s describing. In the Oklahoma chapters of Babb’s novel, the place is not so much a character as the dirt is a character. In Chapter Six, she describes an approaching storm in such detail that I grew anxious as I read it. In Chapter Fourteen, she describes a wall of dust approaching one afternoon and the mad scramble to gather all the children from school. In Chapter Fifteen, the next morning, she describes the dust settled against the windows, making the sunlight look unreal, and going about the task of cleaning up the dirt that covers everything in the house. The dirt is everywhere in Babb’s novel, just like it is everywhere in the characters’ lives—they are breathing it, choking on it, wearing masks and face covers, constantly cleaning up the dirt, clearing off a place to eat a meal in the dirt.

Out of nowhere comes Chapter Seventeen, which is made up entirely of the protagonist Julia’s daily diary entries for the month of April.

“April 4. A fierce dirty day. Just able to get here and there for things we have to do. It is awful to live in a dark house with the windows boarded up and no air coming in anywhere. Everything is covered and filled with dust.”

Then on April 10, Julia describes people looking “like bandits with noses and mouths tied up, faces and hair dirty, and clothes covered. … Said hospitals refuse to operate on anyone unless it’s life or death. Some people getting dust pneumonia.”

That same day, “Noon. Ate on a dirty dusty table. Took up 15 or 20 pounds of dust to make room for more. The dirt is in waves.”

On April 14th, “Dad found Bossy dying this morning. We all did everything we could think of but she was wheezing hard and choking and finally died.”

April 23rd, “Dust. I am sick of writing about it.”

The final entry is April 30th: “Mr. Starwood died. … What a world! Dust is still blowing, sometimes light, sometimes dark. No use to keep on writing dust, dust, dust. Seems it will outlast us.”

By the time the families leave Oklahoma in Chapter Twenty-Five, the reader has a much better sense of what the families are leaving behind and their desperation than one does in The Grapes of Wrath. This makes the hardships and indignities the families suffer in the last third of the novel even more gut-wrenching. It was particularly so for me because, although my grandparents came to California, my great-grandparents stayed in Oklahoma and persevered through the dust storms. My great-grandmother did not come to California until after my great-grandfather died in the 1970s. It is hard to imagine what my great-grandparents suffered and survived.

I would not want to live in a world without The Grapes of Wrath, but I’m glad I had the opportunity to read Whose Names Are Unknown, too. The books are completely different experiences, and what happened to Babb’s writing career is heartbreaking.