Finding Your Way to Plot Through Character

I used to have a plot problem. This is how I solved it.

I recently worked with two writers who had a good sense of the main characters in the novels they were writing. They knew their protagonists inside and out, they knew these characters’ wants and needs, and they knew what the obstacles to their happiness were, but they were struggling to come up with plots. What is the action? What happens to them?

I related … hard. When I first started writing fiction, my stories weren’t really stories. I was more of a character-driven writer versus a plot-driven writer. I’ll admit, at the time I thought it was because my stories were literary—literary stories are more character-driven, and genre stories tend to be more plot-driven. But over time, I learned that all stories need plot. The longer the story, the more plot it needs. A short story can get away with a little less, but a novel needs more to keep readers engaged.

So, I gathered some of the resources that helped me and shared them with my writers, ways to use what they knew about their characters to get at their plot. Today, I’m repurposing those resources to show you how to get to your plot by starting with your protagonist.

“Storytelling is about two things; it’s about character and plot.”

—George Lucas

WHO NEEDS A PLOT?

My early “stories” were character sketches, sometimes with a loose premise. For example, I created a 1980s housewife named Rose who loved couponing, whose husband put her on a strict budget and forbade her to get a job, and who yearned for more. This is a character sketch, but it is not a story.

I gradually added this: thrifty Rose gets so upset that she starts doing something out of character—she starts splurging on shoes and hiding them from her husband. This added some action to the story, but so what? Even this isn’t a story—it’s a premise. But it’s a start, and the story began to grow from this. The story came to fruition when I began to write about what happened as a result of the situations I put Rose in—the things Rose did because of who she is, the decisions she inevitably made because of who she is, and the consequences of those actions and decisions. Only then did I have an engaging, publishable story called “Goody Two Shoes,” a story that was worthy of being named a semifinalist in ScreenCraft’s 2022 Cinematic Short Story Competition.

“This is how I’ve arrived at my plots a number of times. … I would stay with the characters, caring for them, getting to know them better and better, suiting up each morning and working as hard as I could, and somehow, mysteriously, I would come to know what their story was. Over and over I feel as if my characters know who they are, and what happens to them, and where they have been and where they will go, and what they are capable of doing, but they need me to write it down for them because their handwriting is so bad.”

—Anne Lamott, Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life

The better you get to know your characters, the more you begin to know and understand what their stories are—what their stories must inevitably be. If you, like me, lean more toward character than plot, a character sketch isn’t a bad place to start. But you can build on that by putting your character into a situation, knowing exactly how your character would react in that situation, and putting your character through their paces over and over again.

“It’s quite possible to make bread with something other than crushed grain and produce food that’s tasty, nutritious, and solid enough so that you know you’ve eaten something. But whatever your fondness for carrot cake or corn muffins, it’s plain old bread, plot, that’s been part of human culture since the beginning of things.”

—Ansen Dibell, Plot

Once you know your character well enough that you can begin writing about what your character does and about what happens as a result of what your character does, you are on your way to story.

“Plot means the story line. When people talk about plotting, they usually mean how to set up the situation, where to put the turning points, and what the characters will be doing in the end. In brief, they are talking about what happens. Plotting concerns how to move characters in and out of your story. Plotting means what you do to keep the action going. … In a good plot, cause and effect interlink. Each situation sets up the next situation.”

—Jerome Stern, Making Shapely Fiction

Aristotle wrote, ““Plot is character revealed by action.” Two thousand years later, F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote, “Character is plot, plot is character.” They’re both saying the same thing, and they’re both right.

“The king died and then the queen died is a story. The king died, and then the queen died of grief, is a plot.”

—E.M. Forster

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN THERE IS NO PLOT?

Without plot, there isn’t a story. There isn’t narrative drive or cause-and effect trajectory. There are just a bunch of things happening, and that’s meandering and boring and will lose your readers’ attention.

“When poorly conceived, plot creates problems. An over complicated plot can make a book seem contrived or confusing. A lack of plot can make a book seem meandering or static. But plot alone can’t make a fiction vital, witty, moving, informative, or wise. That comes from character, dialogue, description, and narrative style.

“When we call a novel plotless we mean that the writer has not created that interlinking of cause and effect—has not deployed intrigants, developed momentum, or used the traditional narrative devices that seduce and impel readers through the work. … Novelists who eschew plot have captivated readers by their delicious prose, profound meditations, intense visions, and political insights, but the longer the work, the harder it is to keep readers’ attenion all the way to the end.”

—Jerome Stern, Making Shapely Fiction

Your characters must have agency, and this is why. They must be doing things and making decisions, in keeping with who they are and what they want, and the plot will arise out of the consequences of those decisions.

“Plot clearly depends on basic values. What do your characters treasure most? Put it at stake. Let them fight for it. Let them fight for life, love, money, jobs. If your characters care about nothing, the actions around them might become random. Without passion, forget about plot. …

“I am not saying that you must believe in meanings of life and in moral values, but your characters, at least some of them, must. Fiction is like a medieval passion play. If you take away the prospect of crucifixion, the passion, then the play is gone. And passion is why most people read novels.”

—Josip Novakovich, Fiction Writer’s Workshop

I always come back to this—what is at stake for your character? That’s why internal and external desires and needs are so important, because this is what adds meaning to your story. This is what keeps your story from being a character sketch or a premise where nothing vital happens.

HOW CAN YOU GET TO PLOT THROUGH CHARACTER?

It seems hard, I know, but it’s also as simple as this: know your character well (character sketch), put them in a situation (premise), throw some obstacles in their way (the force of opposition), and let them react and do and decide things based on who they are as people.

“A plot can, like a journey, begin with a single step. … You might even say that every novel is a quest novel. The characters will be seeking freedom or truth, revenge or exoneration, peace or sanity. They’re searching for their fathers or mothers or their roots. True love or salvation. Or money, marriage, and success. Or themselves. … [E]verybody’s looking for something.

“The plot grows out of what helps and what hinders the characters’ progress toward their goals.”

—Jerome Stern, Making Shapely Fiction

Your plot will grow from that narrative drive: your character wants something and will do anything to get it because of what’s at stake; someone or something is standing in their way; and because of that your character does something or decides something (good or bad), there are consequences, and then your character must do or decide the next thing.

“You don’t need much to make up a plot. Work from a conflict. … If you have a clear conflict between two (or preferably three or more) characters, everything else will follow ….”

—Josip Novakovich, Fiction Writer’s Workshop

This chain of action on the part of your character is the narrative drive or cause-and-effect trajectory that creates a story, and it continues on through the end, every step of the way arising out of your character’s character, if you will, until it reaches a climax and a resolution.

“Let your human beings follow the music they hear, and let it take them where it will. Then you may discover, when you get close enough to peer into the opening, as if into a scenic Easter egg, that your characters had something in mind all along that was brighter and much more meaningful than what you wanted to impose on them.”

—Anne Lamott, Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life

EXAMPLE OF A CHARACTER-DRIVEN PLOT

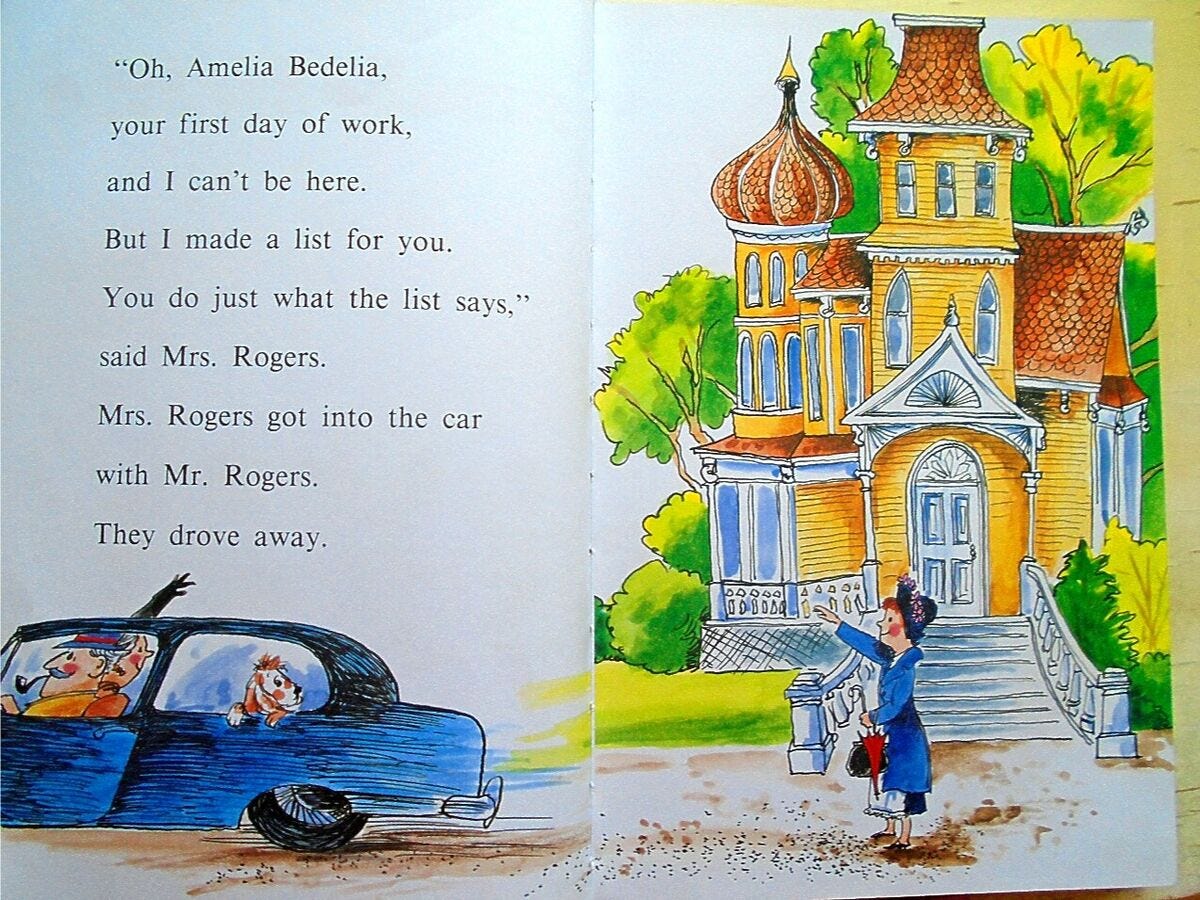

The first character who came to mind when I thought about a character-driven plot was Amelia Bedelia. Amelia Bedelia is the protagonist of a series of books I read in my childhood. She has been super popular for more than 60 years—she recently underwent a contemporary makeover, and my three-year-old granddaughter reads her stories now.

Amelia is the housekeeper for the Rogers family, and the plot of each book is driven by (a) the instructions the Rogers give her for her job; and (b) her character, specifically, her desire to do a good job for her employers and her tendency to take figures of speech literally. If Mrs. Rogers asks her to “dust the furniture,” Amelia Bedelia meticulously covers the furniture with a dusting of powder. If Mrs. Rogers asks her to “draw the drapes,” Amelia Bedelia sits down with a sketch pad and pencil and draws the best picture of the drapes she can. If Mrs. Rogers ask her to “dress the chicken” for supper, Amelia Bedelia sews lovely custom clothes for that chicken and dresses it up in the fancy clothes.

The plot of each story develops completely from who Amelia is—her character—and the resulting disasters. Everything that happens is a result of Amelia being who she is and doing what she does. But the stories always resolve with a happy ending, also because of who Amelia is—charming, good-natured, well-meaning, and a good cook who wins people over with her delicious cookies, cakes, and pies.

This is a simple example, but I think simplest examples are the best. I’ll leave it up to you to make things more complicated for your characters. :)

“The main plot line is simple: Getting your character to the foot of the tree, getting him up the tree, and then figuring out how to get him down again.”

—Jane Yolen

READING & WRITING ROUND-UP

My friend Nick Belardes has a new book coming out this summer and it’s available for preorder now! “Jordan Peele’s Nope meets True Grit in Nicholas Belardes’s Ten Sleep, a supernatural modern-day western about a trio of young people on a 10-day cattle drive that leads them through a canyon haunted by ancient mysteries and savage beasts who existed long before humankind.”

Ten Sleep cover reveal & brief discussion of the American West: Reactor Magazine reveals eco-horror illustration by Brynn Metheney

(Nicholas Belardes for Underwhelmed)

I’m Trying a Wild Experimental Diet Where I Restrict My Working Hours to Certain Times of the Day

(Talia Argondezzi for McSweeney’s Internet Tendency)

Declutter Your Writing Life

(Kate McKean for Agents and Books)

Flashback! [a problem solved]

(Benjamin Dreyer for A Word About…)

Wildfires, dumpster fires, and a keeper of the flame

(Sara Roahen for Memories on the Page)

Free Yourself from Writing Paralysis

(Anne Carley for Jane Friedman)

Complete Novel Roadmap

My friend and fellow book coach Leslie Horn aka Leslie XPLovecat is offering the next 3 spots in her Complete Novel Roadmap program at a $500 discount! A 1-on-1 coaching service designed to take you from scattered ideas to a solid, draft-ready foundation for your novel—in just 8 weeks.

Leanne Phillips

Writer | Book Coach | Editor

leannephillips.com

Thanks for reading my newsletter! If you liked it, please share it with a friend who might enjoy it. If you didn’t enjoy the newsletter, you can unsubscribe below.