The Avila Beach Oil Cleanup

We're working on it, but California has a little fossil fuel problem.

A few days ago, I wrote about July 4, 1997—one of my favorite Independence Day memories. I spent that 4th of July in what was, at the time, a funky little beach town called Avila Beach, located in San Luis Obispo County. I didn’t want to harsh your holiday mellow on Tuesday, but today, I’m going there.

Two years later, in 1999, Unocal (aka Union Oil, parent company Chevron) went into Avila Beach to clean up hydrocarbon contamination caused by underground oil pipes which had, for decades, been seeping oil by-products into the soil underneath the town.

Oil spills and oil contamination are a major ecological concern and health hazard in my beloved home state. California stopped allowing offshore oil drilling along its coast a long time ago. It’s dangerous—seismic and shipping activity can cause pipes that transport oil from platforms to oil pumping stations to rupture, among many other things. But companies outside of California (I’m looking at you, Texas) still own old platforms that are out of reach of California’s jurisdiction and aren’t subject to federal laws prohibiting the sale of new oil leases off California’s coast. Major oil spills have happened even in recent years. In 2015, a corroded pipeline failed and dumped more than 142,000 gallons of oil into the Pacific Ocean at Refugio State Beach, and in 2021, an old pipeline servicing three platforms ruptured off the coast of Long Beach, spilling 126,000 gallons of oil.

The Avila Beach clean-up project required the demolition of all of the businesses facing the beach on Front Street, including the quaint and historic Avila Grocery and Mr. Rick's Beach Bar. Some homes had to be demolished, too. Many townspeople were displaced from their homes and their jobs. Six acres of the delightful little beach town and three and a half acres of the beach itself were excavated. The Inn At Avila Beach was the only business to escape demolition.

The clean-up was completed years ago. Avila Beach is still a charming beach town. Businesses have been reconstructed along Front Street. The Avila Pier was rebuilt. Mr. Rick's Beach Bar and the Avila Grocery reopened their businesses in brand new buildings. The town was reconstructed and rose from the ashes. The buildings are newer, the paint is fresher, and the architecture is more uniform. There are benches, stone walkways, and flower containers lining the beachfront. Many more new businesses have set up shop.

“Perhaps the main moral of Avila Beach’s case study is how untrustworthy oil companies are with the responsibility of monitoring their own facilities, pipes, and operations ….”

—Amanda Ross, “Avila Beach: From Funky to Fabulous,” Focus: The Journal of Planning Practice and Education, Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo (Vol. 12, Issue 1 (2015))

To be honest, it's not quite the same. Some of the unique and funky character of the town was lost in the transformation. But the oil tanks are gone, and that adds so much to the redesigned town’s beauty. My feeling is that the character of a town is shaped mainly by the character of the people who live there, in this case, people who lived through a trying and difficult time, who did not give up, and who saw it through to the end. It’s no longer a town frozen in time in the 1960s, but it’s still something special. During the off-season, townspeople hang out at Mr. Rick's, walk along the beach, or carry on conversations in the town square. In the summertime, visitors flock to the beach for a taste of something simple, natural, and beautiful. Sometimes, I see the Avila Beach I remember slowly taking shape before my eyes again, like a friendly ghost hanging out in the background.

Offshore oil spills damage California’s ecosystems and economy, cause beach closures, kill wildlife, and wreak havoc in the lives of those personally affected. But it’s not just offshore oil production that is hazardous. You’d think Unocal and other oil companies would have learned something from disasters like these, but they haven’t. They wait to do the right thing until they’re forced to. The law firm I work for just won a $63 million verdict against Unocal for delaying a cleanup underneath our client’s home for 41 years, which resulted in our client being poisoned by benzene and developing terminal blood cancer: Santa Maria Jury Hammers Chevron with $63 Million Verdict: Oil Company Waited 41 Years to Clean Up ‘Hazardous Cesspool’. $41 million of the award was punitive damages—$1 million for every year Unocal had delayed cleaning up its mess.

I could go on and on, citing more cases like these, even in San Luis Obispo County. They’re all reminiscent of Grisham vs. Ford Motor Company (1981), a lawsuit born out of the tendency of late ’60s/early ’70s Ford Pintos to catch fire and engulf their passengers in flames when they were rear-ended.1 A memo was unearthed during discovery proving that the company made a calculated decision: it would be less expensive to pay out on a few wrongful death claims than it would be to fix the defect, even at $1 per vehicle. “Simply, Ford's internal ‘cost-benefit analysis,’ which places a dollar value on human life, said it wasn't profitable to make the changes sooner. Ford's cost-benefit analysis showed it was cheaper to endure lawsuits and settlements than to remedy the Pinto design.” (American Museum of Tort Law, “Grimshaw v. Ford Motor Company, 1981.”)

Unsurprisingly, oil companies seem to make the same kinds of decisions. The 1999 Avila Beach clean up project ultimately cost Unocal an estimated $200 million dollars, but in the years prior to the clean up, they were posting much more than that in profits year after year after year, as well as earning interest on the money they declined to use to remedy their mistakes. Now owned by Chevron, Unocal’s parent company posted more than $35 billion in profits last year. Oil companies have declined to make the lives of their customers any easier during and post-pandemic by releasing stockpiled oil or lowering gas prices to a reasonable level, opting to exploit consumers and earn ridiculous profit margins. But neither did they take some of that bonus money and clean up the messes they’ve made. Instead, they’ll hang onto it and keep earning interest until they’re forced into action, each and every time.

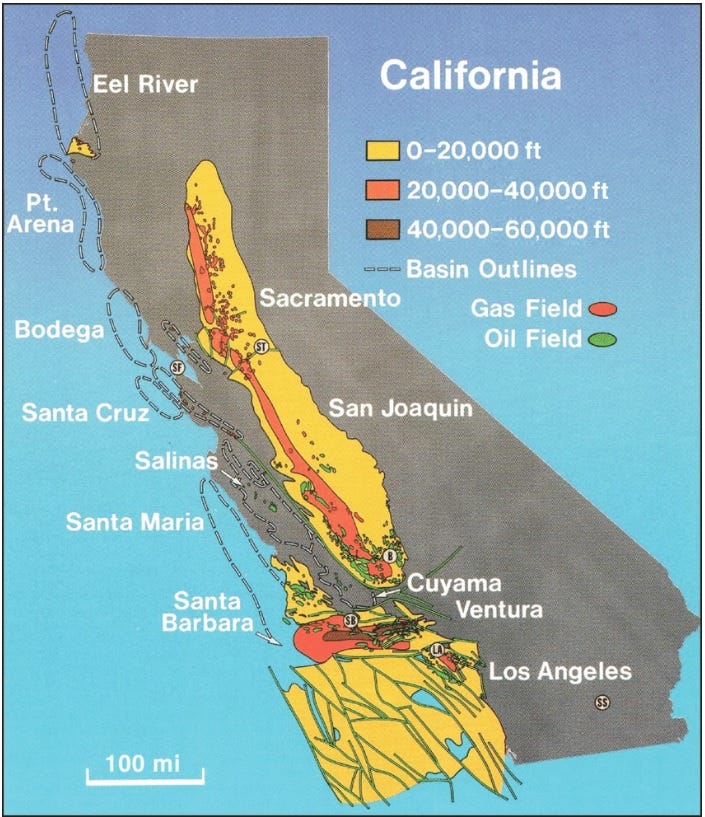

California is the 7th top oil-producing state in the country. In 1903 and off-and-on through 1930, it was the leading oil producing state. It’s heavy oil reserves are “second only to Venezuela” (Frances J. Hein, abstract, “Overview of Heavy Oil, Seeps, and Oil (Tar) Sands, California”) 70% of the oil produced in California is produced in Kern County. The “Kern River Oil Field ... [is] the most dense oilfield in the United States” (World Atlas, “America’s top 10 Oil Producing States”). So it’s not just off-shore oil or out-of-state operations that are the problem. An estimated 929 oil and gas companies are operating in California—oil is everywhere.

California is taking great strides toward reducing its dependence on fossil fuels, but it can’t come soon enough. As long as oil production continues in California and oil companies fail and refuse to clean up contaminations and remove, repair, or replace old equipment, California’s citizens, municipalities, and wildlife are at risk.

My dad had a Ford Pinto in the 1970s. Classic my Dad. His was filled with smoke too but from his chain-smoking rather than a gas tank fire. He battled that addiction all of his life, trying to replace cigarettes with lemon drops time and time again. But the addiction won and eventually took his life in the form of lung cancer. The tobacco industry is another case of corporations valuing profits over human lives, but that’s another rant for another time.